Story by Marcia Brown, Foundations of Success

All around us, we increasingly see evidence that the climate is changing: rising temperatures, glaciers melting, larger wildfires, sea levels rising, shifting precipitation patterns, and oceans becoming more acidic. As conservation coaches, we have typically treated climate change as a direct threat that we put into a pink threat box in our conceptual models and, inevitably, rated as very high. Over time, many of us have found that treating climate change as just another direct threat hasn’t been helpful. Why?

- This approach doesn’t enable us to grapple will the uncertainty related to climate change. In many cases, we don’t know if our conservation area will get wetter or drier, if temperatures will warm gradually or increase dramatically, or how species and ecosystems will respond to these changes.

- It doesn’t allow us to describe how, based on the best available evidence, we believe that climate change will affect our conservation targets and interact with other direct threats.

- It doesn’t allow us to consider how humans will respond to climate change and if this will exacerbate existing threats or create new ones (e.g., pumping more groundwater in response to droughts, building seawalls, etc.).

- Without being able to do any of the above, we are limited in our ability to develop climate-smart strategies.

As conservation professionals, we are accustomed to looking to the past when we set our goals. For example, we want our salmon streams to be as productive as they were in the 19th century, we want to rebuild forest connectivity and to bring the populations of endangered species back to former, healthier levels. Yet, because of climate change, the future is apt to be different from the past–but we don’t know how different it will be.

We need to more adequately incorporate climate change into our conservation planning and adaptive management. To address this need, several coaches have been working together over the past few years to make the Open Standards “climate-smart.” We use the term “climate-smart conservation” because we believe that all conservation should be done in a way that considers climate change. The National Wildlife Federation (NWF) defines “climate-smart conservation” as: “the intentional and deliberate consideration of climate change in natural resource management, realized through adopting forward-looking strategies to key climate impacts and vulnerabilities.”[1]

We have reviewed guidance documents produced by various conservation NGOs and agencies and found the NWF guide to be particularly valuable. Four overarching themes frame NWF’s definition of climate-smart conservation:

- Act with intentionality – carry out climate adaptation in a purposeful and deliberate manner that explicitly considers the potential impacts of climate change on ecosystems and species of interest and links conservation actions to these impacts

- Manage for change, not just persistence – Given current trends, conservation will need to shift from emphasizing preservation and historical restoration to anticipating and actively facilitating ecological transitions.

- Reconsider goals, not just strategies – As conditions change, some of our conservation goals and objectives may no longer be achievable. In addition to adjusting strategies to meet our goals, we will need to reevaluate, and revise as appropriate, our underlying conservation goals.

- Integrate adaptation into existing work – To date, climate adaptation work has focused more on planning than implementation. One of the best ways to encourage more implementation is to integrate climate adaptation into existing work, so that it is not perceived as something separate from conservation.

Climate-smart Open Standards

We are proposing several adjustments to the Open Standards to make them climate-smart. Although climate change is complex, we have worked to make our recommendations as practical as possible, because we understand that project teams have limited time to invest in conservation planning.

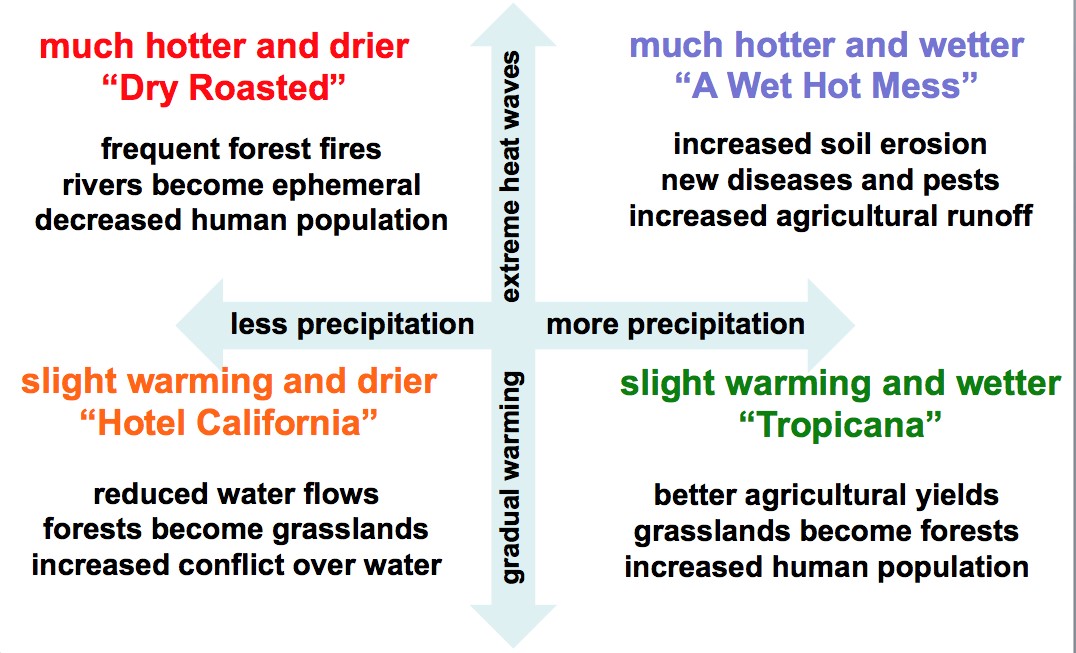

The process we are proposing for climate-smart Open Standards is described in Table 1. The inital steps (1-3) are mostly a standard application of the Open Standards. After defining their project scope, vision and targets, the conservation team should complete their viability assessment and add conventional direct threats to their conceptual model. The only difference is that the viability assessment should not include defining the desired future state of the indicators for the key ecological attributes. We recommend doing this later, once the team has assessed climate vulnerability.

Table 1. Proposed Climate-smart Open Standards Process

Steps 4-6 focus on conducting a climate vulnerability assessment, using climate scenario planning, climate conceptual models and threat rating. The addition of climate scenario planning represents the biggest change we are proposing. Scenario planning is a decision support tool that has been used extensively by the military and businesses. It is designed to help address situations with high uncertainty, complexity and impact and low controllability. It provides a framework for considering multiple plausible futures – stories or hypotheses, not predictions or projections. It helps answer questions such as:

- How will climate change affect our conservation targets?

- What species and ecosystems are most vulnerable?

- How will species’ range shift? How will ecosystem composition change, as species move latitudinally and altitudinally?

- How will climate change interact with conventional direct threats?

- How will people respond to climate change and will this exacerbate existing threats or pose new ones?

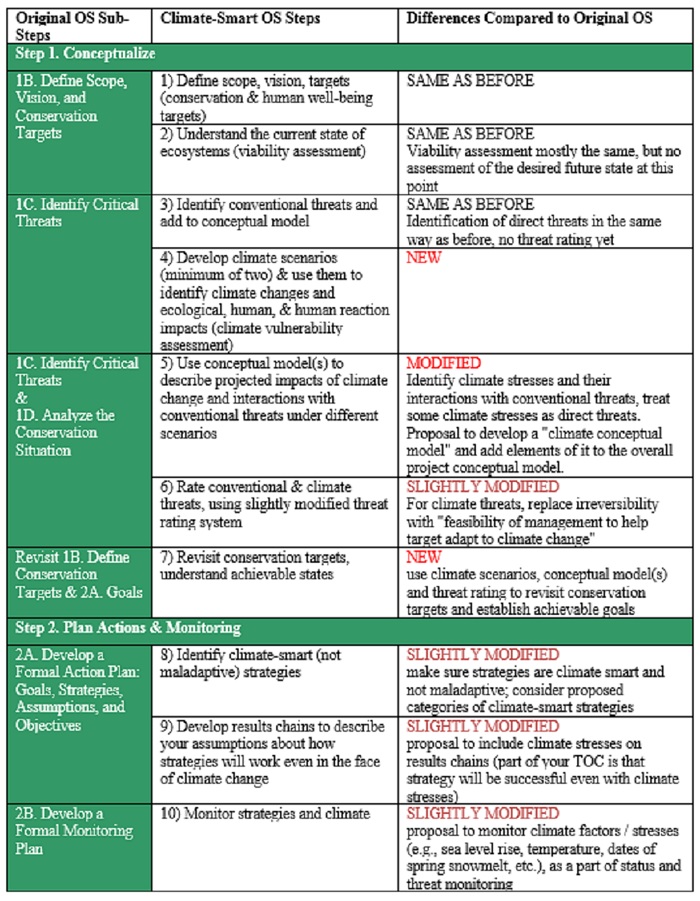

For teams who do not have access to site-specific climate modeling data, we recommend that they use Climate Wizard, a tool that enables technical and non-technical audiences alike to easily and intuitively access information about how climate has changed over time and to project what future changes are likely to occur in a given area. We recommend that practitioners use Climate Wizard to identify at least two important variables with high uncertainty (such as temperature and precipitation). These variables then become the axes in a quadrant map containing four plausible future climate scenarios. Figure 1 shows an example of a relatively simple climate scenario quadrant map.

Figure 1. Example Climate Scenario Quadrant Map

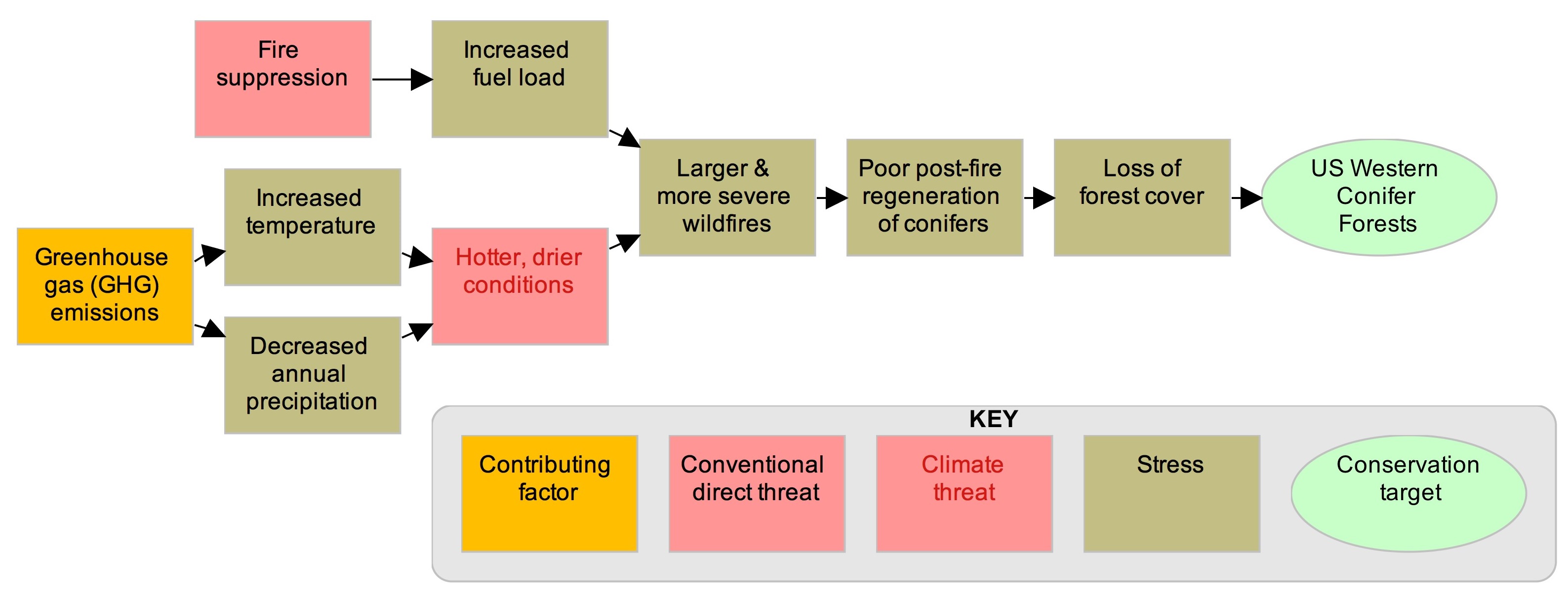

Step 5 involves developing one or more “climate conceptual models” to describe the projected impacts of climate change and interactions with conventional threats under different scenarios. As shown in Figure 2, climate conceptual models include targets, conventional direct threats, stresses and “climate threats,” which technically are climate stresses that we are treating as direct threats so that we can include them in the threat rating. When the team completes their overall project conceptual model (with contributing factors), they will probably want to include the most important elements of these climate conceptual models in their overall model.

When rating direct threats (Step 6), we recommend rating both conventional direct threats (e.g., fire suppression) and climate threats (e.g., hotter, drier conditions). We recommend adapting the rating criteria a bit for climate threats.

Once the team has completed their climate vulnerability assessment (steps 4-6), we recommend that teams use their climate scenarios, conceptual model(s) and threat ratings to revisit their conservation targets and establish ambitious but achievable goals. During this process, the team may determine, for example, that the composition of their forest ecosystems is likely to change or that it will become increasingly difficult to prevent the loss of montane plants or an endangered butterfly. Their goals will need to take these projected changes into account.

Figure 2. Simple Climate Conceptual Model

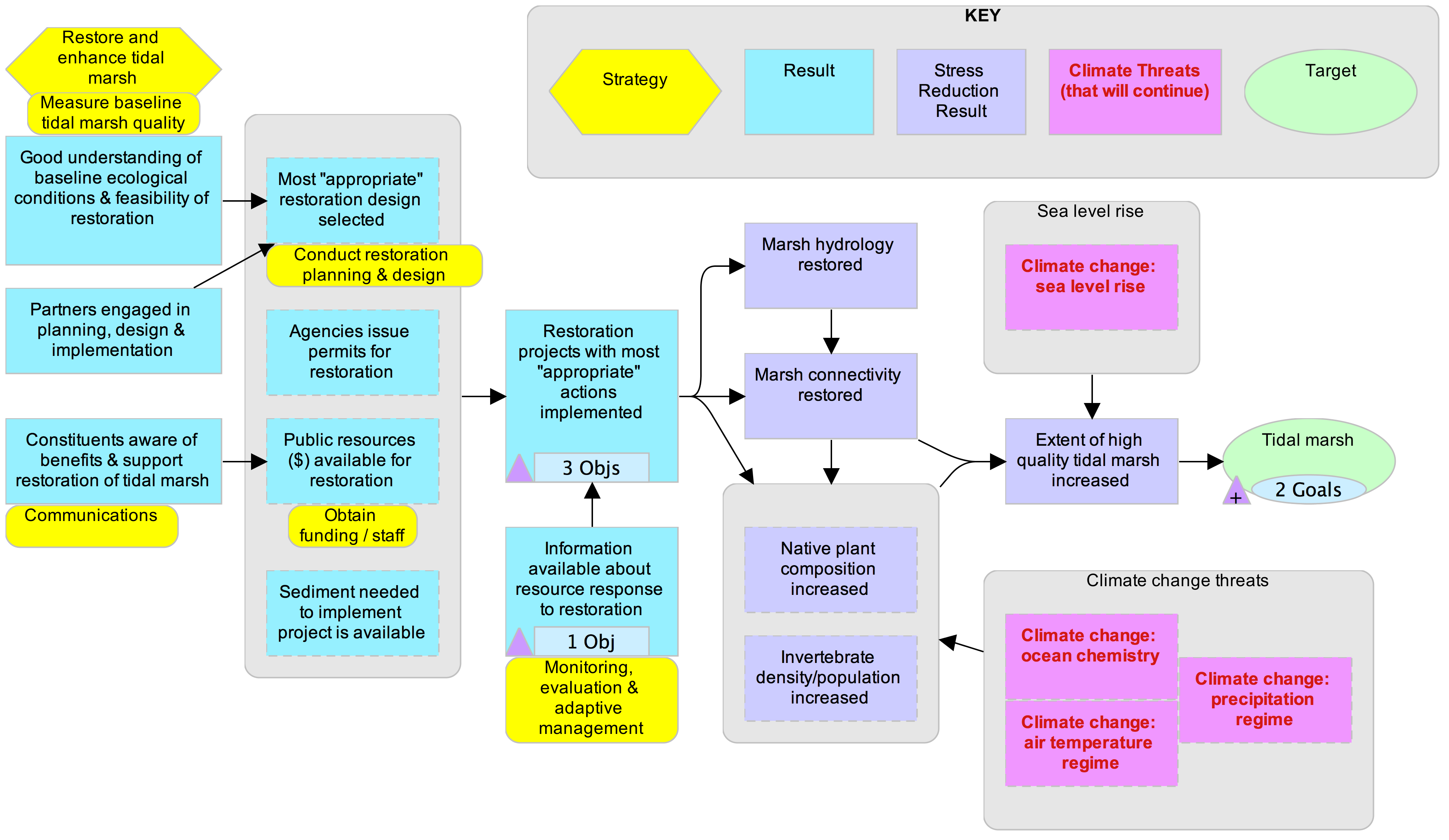

To assist teams in brainstorming and selecting climate-smart (not maladaptive) strategies (Step 8), we have developed categories of climate-smart strategies to consider. When developing results chains (Step 9), we encourage teams to consider including stress reduction results (e.g., marsh connectivity restored) and keeping climate threats such as “sea level rise” in the model (see Figure 3). An important part of your theory of change is that your strategy will be successful even as climate stresses continue to affect your conservation targets. Finally, we propose monitoring climate factors or stresses (e.g., sea level rise, temperature, the dates of spring snowmelt, etc.) as part of your status and threat monitoring (Step 10).

For more information about Climate-smart Open Standards or to provide feedback, please contact Marcia Brown and John Morrison. All of the materials prepared for the Climate-smart OS sessions at the CCNet Rally 2018 and recordings of the webinars we organized after the Rally are available here.

Figure 3. Example Results Chain With Stress Reduction Results and Climate Threats. Adapted from results chains developed by the US Fish & Wildlife Service’s San Francisco Bay National Wildlife Refuge Complex Team

[1] Stein, B.A, P. Glick, N. Edelson, and A. Staudt (eds.). 2014. Climate-smart Conservation: Putting Adaptation Principles into Practice. National Wildlife Federation, Washington, D.C.